Composer: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (b. 1756 - d. 1791)

Performance date: 01/07/2010

Venue: St. Brendan’s Church

Composition Year: 1789

Duration: 00:33:09

Recording Engineer: Anton Timoney, RTÉ lyric fm

Instrumentation: 2vn, va, vc

Instrumentation Category:Clarinet Quintet

Instrumentation Other: 2vn, va, vc, bcl

Artists:

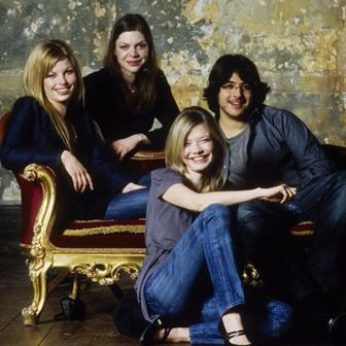

Chiaroscuro Quartet (Alina Ibragimova, Pablo Hernán Benedí [violins], Emilie Hörnlund [viola], Claire Thirion [cello]) -

[quartet]

Chen Halevi -

[basset clarinet]

It is inevitable that composers are

inspired to write works for specific individuals or ensembles. In the

most obvious cases, virtuoso composers write works for themselves,

especially early in their careers. Beethoven and Mozart were both

superb keyboard players and wrote works that they would then premiere

themselves, most especially in the case of Mozart’s piano concertos.

Much would depend on the composer’s primary source of income and

their facility of composition. Brahms, famously, never composed to

commission, but was able to make his living from a combination of

performance honorariums and publication fees. This meant he was at

liberty to compose whatever he wanted and most of his chamber works

would have been written with specific performers in mind. Today

composers rely heavily on commissions, which means that they often

have the performers chosen for them.

Mozart made his living in the most

hazardous way with an erratic combination of performance and

publication fees, with his cash-flow problems subsidised in the

modern manner by heavy borrowing, especially from fellow Freemasons.

Unlike Beethoven he never managed to secure rich and reliable patrons

and unlike Haydn he never had a secure salaried post. However, like

Schubert, who was similarly impecunious, he composed at great speed.

So when Mozart was in the middle of composing and producing Cosi

fan Tutti in the autumn of 1789, he could still find time to turn

aside from this and write a quintet for his friend Anton Stadler, the

famous clarinettist.

They had met by 1784 as Stadler is

known to have taken part in the premiere of the Gran Partita in March

of that year. After that they often worked together and Stadler would

have played in the various orchestras that premiered Mozart’s

symphonies, concertos and operas. Stadler was also a Freemason, so,

when he requested a new work for a Christmas concert, Mozart set

aside the opera and got to work. There was another musical reason for

Mozart’s interest in writing a quintet, Stadler had recently invented

a new instrument known as a basset clarinet. No example of it

survives, but it was known to extend the range of the normal clarinet

by a major third. Unfortunately Mozart’s autograph score has not

survived, but the original version and the unusual instrument have

been reliably reconstructed and this is what we hear today.

The Clarinet Quintet has several

features that are also found in the Prussian Quartets. Just as the

cello, in the first Prussian Quartet, is slow to reveal the prominent

role it is going to play, so does the clarinet for a surprisingly

long time play only unimportant material. In the first subject it

bridges gaps between string phrases and only gets to play out in the

second, less important part, of the first-subject group. The second

subject is given to the first violin alone, until the clarinet

eventually takes it over as the music changes to the minor mode. This

temporary darkening of the A major mode allows the clarinet to show

off its wonderful range of colours.

The graceful Larghetto gives the

clarinet the opportunity to display its lyrical qualities to the

full, especially in the magical, flowing melody that opens the

movement. This is music to fall in love to, time cannot quench its

beauty and, at every hearing, Mozart weaves his unique spell. The

double minuet awakens us from our trance and the clarinet is allowed

to retire during the first trio, given to the strings alone. The

witty finale is a theme and five variations with a coda. As in the

first movement the solo instrument must, in the true spirit of

chamber music, wait to take its turn. The chirpy theme is stated by

the two violins and the clarinet is confined to brief cadential

flourishes. So in the first variation the clarinet is given the

theme, and in the second variation it is the turn of the viola and

cello. The third variation is traditionally in the minor key and here

the dark colour of the viola is given first place. After this the two

violins take charge while the clarinet dances delightedly around

them. Finally we come to the Adagio variation and again the strings

begin without the clarinet, who later melts into the texture. The

Allegro coda is a joyful summary of the spirit of the theme.

Copyright © 2025 West Cork Music. All rights reserved.

Designed and developed by Matrix Internet